Programming with Python

Analyzing Temperature Data

Learning Objectives

- Explain what a library is, and what libraries are used for.

- Load a Python library and use the things it contains.

- Read tabular data from a file into a program.

- Assign values to variables.

- Select individual values and subsections from data.

- Perform operations on arrays of data.

- Display simple graphs.

While a lot of powerful tools are built into languages like Python, even more live in the libraries.

In order to load our temperature data, we need to import a library called NumPy. In general you should use this library if you want to do fancy things with numbers, especially if you have matrices or arrays. We can load NumPy using:

import numpyImporting a library is like getting a box of lab equipment out of a storage locker, inventorying the contents, and setting the box on the bench. Libraries provide additional functionality to Python just like a new piece of equipment adds functionality to a lab space. Once we’ve loaded the library, we can use NumPy to read the data file:

numpy.loadtxt('data/temperature.csv', delimiter=',')array([[ 264., 264., 264., ..., 263., 263., 264.],

[ 263., 264., 264., ..., 262., 262., 263.],

[ 301., 302., 302., ..., 301., 301., 301.],

[ 292., 293., 293., ..., 291., 292., 292.]])The expression numpy.loadtxt(...) is a function call that tells Python to run the function loadtxt from the numpy library. This dotted notation, with the syntax thing.component, is used everywhere in Python to refer to the parts of things.

The function call to numpy.loadtxt has two parameters: the name of the file we want to read and the delimiter that separates values on a line. Both need to be character strings (or strings for short) so we write them in quotes.

Within the Jupyter iPython notebook, pressing Shift+Enter runs the commands in the selected cell. Because we haven’t told iPython what to do with the output of numpy.loadtxt, the notebook just displays the output to the screen. In this case, the output is the data we loaded from the temperature file. By default, only a few rows and columns are shown (with ... to omit elements when displaying big arrays). To save space, Python displays numbers as 1. instead of 1.0 when there’s nothing interesting after the decimal point.

The function call numpy.loadtxt read the temperature file but didn’t save it somewhere we can access it. In order to use the data within Python, we need to assign assign the array to a variable. A variable is just a name that refers to an object. Python’s variables must begin with a letter and are case sensitive. We can assign a variable name to an object using =.

To fully understand what variables and objects are related, let’s consider the simplest “collection” of data: a single value. The line below assigns the value 55 to a variable weight_kg:

weight_kg = 55Once a variable is assigned to an object, we can print the value in the object to the screen:

print weight_kg55and do arithmetic with it:

print 'weight in pounds:', 2.2 * weight_kgweight in pounds: 121.0We can also change a variable’s value by assigning it a new one:

weight_kg = 57

print 'weight in kilograms is now:', weight_kgweight in kilograms is now: 57As the example above shows, we can print several things at once by separating them with commas.

If we imagine the variable as a sticky note with a name written on it, ]variable assignment](reference.html#assignment) is like putting the sticky note on a particular box containing some information:

Variables as Sticky Notes

This means that assigning a value to any one variable does not change the values of objects associated with other variables. For example, let’s store the subject’s weight in pounds in a variable:

weight_lb = 2.2 * weight_kg

print 'weight in kilograms:', weight_kg, 'and in pounds:', weight_lbweight in kilograms: 57 and in pounds: 125.4Creating Another Variable

and then change weight_kg:

weight_kg = 100.0

print 'weight in kilograms is now:', weight_kg, 'and weight in pounds is still:', weight_lbweight in kilograms is now: 100.0 and weight in pounds is still: 125.4Updating a Variable

Since the variable name weight_lb doesn’t “remember” how it came to be associated with “125.4”, its value isn’t automatically updated when weight_kg changes. This is different from the way spreadsheets work, where changing the value of a cell cascades to any values that are calculated from it.

Just as we can assign a single value to a variable, we can also assign an array of values to a variable using the same syntax. Let’s re-run numpy.loadtxt and assign the output of the function call to a variable:

data = numpy.loadtxt('data/temperature.csv',delimiter=',')This statement doesn’t produce any visible output but we can look at the object using print:

print data[[ 264. 264. 264. ..., 263. 263. 264.]

[ 263. 264. 264. ..., 262. 262. 263.]

[ 301. 302. 302. ..., 301. 301. 301.]

[ 292. 293. 293. ..., 291. 292. 292.]]By default, the temperature data has units of 10ths of a degree Fahrenheit. Let’s load it again and convert it to degrees Fahrenheit by dividing every item in the array by 10. To avoid accidentally introducing errors through integer division, we should divide the data by a float just in case the data imports as integers. These small details make your code more robust and reusable!

data = numpy.loadtxt('data/temperature.csv',delimiter=',') / 10.

print data[[ 26.4 26.4 26.4 ..., 26.3 26.3 26.4]

[ 26.3 26.4 26.4 ..., 26.2 26.2 26.3]

[ 30.1 30.2 30.2 ..., 30.1 30.1 30.1]

[ 29.2 29.3 29.3 ..., 29.1 29.2 29.2]]Check your understanding

Draw diagrams showing what variables refer to what values after each statement in the following program:

mass = 47.5

age = 122

mass = mass * 2.0

age = age - 20Sorting out references

What does the following program print out?

first, second = 'Grace', 'Hopper'

third, fourth = second, first

print third, fourthLet’s see what type of object the variable data refers to:

print type(data)<class 'numpy.ndarray'>The output tells us that data currently refers to an N-dimensional array created by the NumPy library. We can see what its shape is like this:

print data.shape(4, 365)This tells us that data has 4 rows and 365 columns. This array contains daily average temperature normals (data averaged over 30 years) for four weather stations around Flagstaff, AZ. The rows are the individual stations and the columns are the average temperatures for each day of the year.

The object associated with the variable data contains not just the values in the array but also information about the array. These are the members or attributes. This extra information describes data in the same way an adjective describes a noun: data.shape is an attribute of data that described the dimensions of data. We use the same dotted notation for the attributes of variables that we use for the functions in libraries because they have the same part-and-whole relationship.

If we want to pull a single number from the array, we use the index of that entry in square brackets:

print 'first value in data:', data[0, 0]first value in data: 26.4print 'middle value in data:', data[2, 180]middle value in data: 69.6An index like [2, 180] selects a single element of an array, but we can select whole sections as well. A section of an array is called a slice. For example, we can select the first ten days (columns) of values for the first two stations (rows) like this:

print data[0:2, 0:10][[ 26.4 26.4 26.4 26.5 26.5 26.6 26.6 26.6 26.7 26.7]

[ 26.3 26.4 26.4 26.5 26.5 26.6 26.6 26.7 26.7 26.8]]

The slice 0:2 means, “Start at index 0 and go up to, but not including, index 2.” Again, the up-to-but-not-including takes a bit of getting used to, but the rule is that the difference between the upper and lower bounds is the number of values in the slice.

We don’t have to start slices at 0:

print data[2:4, 0:10][[ 30.1 30.2 30.2 30.2 30.3 30.3 30.4 30.4 30.5 30.6]

[ 29.2 29.3 29.3 29.4 29.4 29.5 29.5 29.6 29.6 29.7]]We don’t always have to include the upper and lower bound on the slice. If we don’t include the lower bound, Python uses 0 by default; if we don’t include the upper, the slice runs to the end of the axis, and if we don’t include either (i.e., if we just use ‘:’ on its own), the slice includes everything:

small = data[:2,360:]

print 'small is:'

print smallsmall is:

[[ 26.3 26.3 26.3 26.3 26.4]

[ 26.1 26.1 26.2 26.2 26.3]]Slicing strings

We can take slices of character strings as well:

element = 'oxygen'

print 'first three characters:', element[0:3]

print 'last three characters:', element[3:6]first three characters: oxy

last three characters: genWhat is the value of element[:4]? What about element[4:]? Or element[:]?

What is element[-1]? What is element[-2]? Given those answers, explain what element[1:-1] does.

We can perform common mathematical operations on arrays and create new ones with the results. The simplest operations with data are arithmetic: add, subtract, multiply, and divide. When you do such operations on arrays, the operation is done on each individual element of the array. Thus:

doubledata = data * 2.0will create a new array doubledata whose elements have the value of two times the value of the corresponding elements in data:

print 'original:'

print data[:2,360:]

print 'doubledata:'

print doubledata[:2,360:]original:

[[ 26.3 26.3 26.3 26.3 26.4]

[ 26.1 26.1 26.2 26.2 26.3]]

doubledata:

[[ 52.6 52.6 52.6 52.6 52.8]

[ 52.2 52.2 52.4 52.4 52.6]]We can also perform mathematical operations using two arrays of the same size. In that case, The operation will use the corresponding elements of each of the two arrays. Thus:

tripledata = doubledata + datawill give you an array where tripledata[0,0] = doubledata[0,0] + data[0,0] and so on for all other elements of the arrays.

print 'tripledata:'

print tripledata[:2,360:]tripledata:

[[ 78.9 78.9 78.9 78.9 79.2]

[ 78.3 78.3 78.6 78.6 78.9]]We can also perform statistical operations on arrays. If we want to find the average temperature on all days across all stations, for example, we can just ask the array for its mean value

print data.mean()45.783767123mean is a method of the array, i.e., a function that belongs to it in the same way that the member shape does. If variables are nouns, methods are verbs: they are operations that the object can perform. We write data.mean() with empty parenthesis because it is a request to the object data for an action. data.shape doesn’t need them because it is just a “characteristic” of data.

NumPy arrays have lots of useful methods:

print 'maximum temperature:', data.max()

print 'minimum temperature:', data.min()

print 'standard deviation:', data.std()maximum temperature: 71.4

minimum temperature: 26.1

standard deviation: 13.379753803When analyzing data, we often want to look at partial statistics such as the maximum value per station or the average value per day. One way to do this is to create a new temporary array that contains just the data we want and then look at the statistics of the full sub-array:

station_0 = data[0, :] # 0 on the first axis, everything on the second

print 'maximum temperature for station 0:', station_0.max()maximum temperature for station 0: 64.1We don’t actually need to store the row in a variable of its own. Instead, we can combine the selection and the method call:

print 'maximum temperature for station 2:', data[2, :].max()maximum temperature for station 2: 71.4If we need the maximum temperature for every stations or the average for each day across all four stations, we can perform the operation across an axis. Most array methods allow us to specify the axis we want to work on. If we ask for the average across axis 0 (rows in our 2-D example), we get:

print data.mean(axis=0)[ 28. 28.075 28.075 28.15 28.175 28.25 28.275 28.325 28.375

28.45 28.475 28.55 28.6 28.675 28.7 28.75 28.825 28.875

28.925 29. 29.05 29.075 29.175 29.2 29.275 29.35 29.4

29.5 29.575 29.625 29.7 29.825 29.875 29.975 30.075 30.175

30.25 30.375 30.5 30.6 30.75 30.9 31.05 31.175 31.325

31.475 31.65 31.8 31.975 32.125 32.3 32.5 32.65 32.825

33.025 33.2 33.4 33.575 33.75 33.95 34.125 34.325 34.525

34.725 34.875 35.075 35.275 35.45 35.625 35.8 35.975 36.15

36.325 36.5 36.65 36.825 37.025 37.15 37.325 37.5 37.65

37.825 38. 38.2 38.35 38.525 38.725 38.9 39.075 39.275

39.45 39.65 39.85 40.05 40.275 40.5 40.7 40.9 41.2

41.4 41.65 41.9 42.175 42.425 42.675 42.95 43.2 43.5

43.75 44.05 44.325 44.6 44.9 45.2 45.475 45.775 46.05

46.35 46.6 46.925 47.2 47.5 47.775 48.075 48.325 48.6

48.9 49.125 49.4 49.65 49.925 50.175 50.425 50.675 50.95

51.15 51.4 51.65 51.9 52.15 52.375 52.625 52.85 53.1

53.325 53.575 53.825 54.1 54.325 54.575 54.85 55.1 55.375

55.65 55.925 56.2 56.475 56.775 57.075 57.35 57.65 57.95

58.25 58.55 58.875 59.175 59.5 59.8 60.15 60.45 60.75

61.05 61.35 61.675 61.975 62.25 62.525 62.825 63.075 63.35

63.6 63.85 64.05 64.275 64.475 64.7 64.9 65.05 65.2

65.35 65.475 65.6 65.7 65.8 65.875 65.925 65.975 66.025

66.05 66.05 66.05 66.05 66.025 66. 65.95 65.925 65.825

65.8 65.725 65.625 65.575 65.45 65.375 65.275 65.175 65.075

64.95 64.85 64.75 64.65 64.55 64.425 64.3 64.2 64.075

63.975 63.825 63.725 63.575 63.475 63.325 63.2 63.075 62.95

62.8 62.675 62.525 62.35 62.175 62.025 61.85 61.675 61.475

61.3 61.05 60.85 60.65 60.375 60.175 59.9 59.65 59.35

59.1 58.825 58.5 58.2 57.875 57.575 57.2 56.875 56.5

56.15 55.775 55.425 55.05 54.675 54.3 53.925 53.5 53.175

52.75 52.35 52. 51.575 51.225 50.825 50.45 50.075 49.675

49.325 48.975 48.6 48.275 47.875 47.55 47.2 46.875 46.55

46.2 45.9 45.575 45.25 44.95 44.625 44.325 44. 43.7

43.4 43.15 42.85 42.55 42.25 41.925 41.625 41.325 41.025

40.725 40.375 40.075 39.775 39.425 39.125 38.775 38.45 38.125

37.775 37.45 37.1 36.75 36.425 36.05 35.725 35.375 35.025

34.7 34.35 34. 33.7 33.325 33. 32.675 32.35 32.05

31.775 31.475 31.175 30.925 30.675 30.4 30.175 29.925 29.75

29.525 29.325 29.125 28.975 28.85 28.7 28.575 28.45 28.325

28.25 28.15 28.1 28.05 28.025 27.975 27.95 27.95 27.9

27.9 27.925 27.925 27.95 28. ]As a quick check, we can ask this array what its shape is:

print data.mean(axis=0).shape(365,)The expression (365,) tells us we have an N×1 vector, so this is the average temperature per day for all stations. If we average across axis 1 (columns in our 2-D example), we get:

print data.mean(axis=1)[ 43.8430137 43.00684932 49.98767123 46.29753425]which is the average temperature per station across all days.

Plotting

The mathematician Richard Hamming once said, “The purpose of computing is insight, not numbers,” and the best way to develop insight is often to visualize data. Visualization deserves an entire lecture (or course) of its own, but we can explore a few features of Python’s matplotlib library here. While there is no “official” plotting library in Python, this package is the de facto standard.

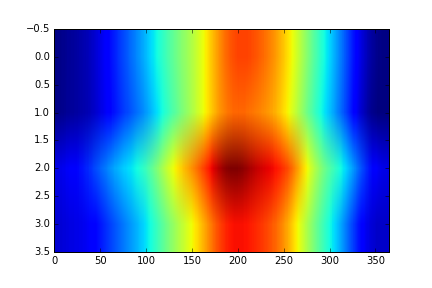

First, we will import the pyplot module from matplotlib and use two of its functions to create and display a heat map of our data:

import matplotlib.pyplot

image = matplotlib.pyplot.imshow(data)

matplotlib.pyplot.show(image)

Heatmap of the Data

It’s very hard to see what the image shows when it’s that small. Let’s change the aspect ratio:

image = matplotlib.pyplot.imshow(data)

matplotlib.pyplot.axes().set_aspect('auto')

matplotlib.pyplot.show(image)

Heatmap of the Data with different aspect ratio

Blue regions in this heat map are low values, while red shows high values. As we can see, temperature rises and falls over the year.

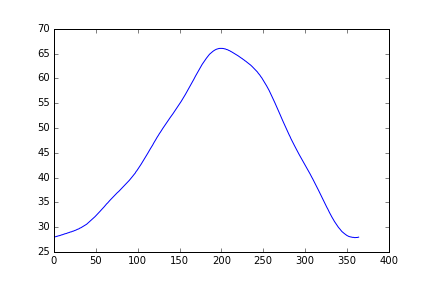

Let’s take a look at the average temperature between all the stations over time by making a line plot:

ave_temp = data.mean(axis=0)

ave_plot = matplotlib.pyplot.plot(ave_temp)

matplotlib.pyplot.show(ave_plot)

Average Temperature Over Time

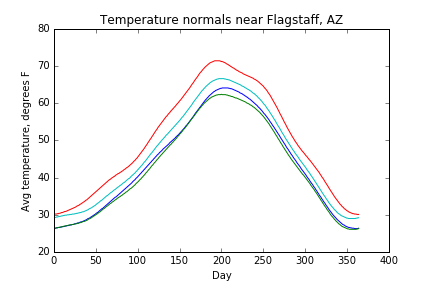

It’s interesting to examine how the temperature trends vary between stations throughout the year. We can make four different line plots that show the data from each of the stations separately. To summarize what we’ve learned so far, let’s write every command we need to import the data and create the plots:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

data = np.loadtxt('data/temperature.csv', delimiter=',') / 10.

plt.plot(data[0,:])

plt.show()

plt.plot(data[1,:])

plt.show()

plt.plot(data[2,:])

plt.show()

plt.plot(data[3,:])

plt.show()It is still difficult to compare the temperature between stations with these plots. Instead, let’s plot the data for all each of the stations separately in the same plot. We can include the argument hold=True the first time we call plt.plot to force all subsequent calls to plt.plot to use the same axes (until it reaches plt.show()). We can add labels to the axes using the xlabel() and ylabel() functions and the title with title().

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

data = np.loadtxt('data/temperature.csv', delimiter=',') / 10.

plt.plot(data[0,:], hold=True)

plt.plot(data[1,:])

plt.plot(data[2,:])

plt.plot(data[3,:])

plt.xlabel('Day')

plt.ylabel('Avg temperature, degrees F')

plt.title('Temperature normals near Flagstaff, AZ')

plt.show()

Temperature for each of the four stations

Make your own plot

Create separate plots showing the maximum (numpy.max()), minimum (numpy.min()), and standard deviation (numpy.std()) of the temperature data for each day across all stations. Label the axes and include a title for each of them.

Convert the separate plots into a single plot that includes all three statistics (using hold=True).

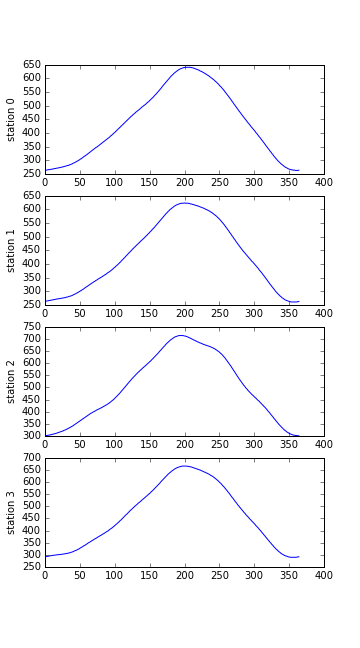

Subplots

To better visualize data, we often want to arrange separate plots in layouts with multiple rows and columns. The script below plots the data from each of the stations separately in a single figure using subplots. Type the code for yourself so you get a sense of what it does.

This script uses a number of new commands. The function matplotlib.pyplot.figure() creates a space into which we will place all of our plots. The parameter figsize tells Python how big to make this space. Each subplot is placed into the figure using the subplot command. The subplot command takes 3 parameters. The first denotes how many total rows of subplots there are, the second parameter refers to the total number of subplot columns, and the final parameters denotes which subplot your variable is referencing. Each subplot is stored in a different variable (axes1, axes2, axes3, axes4). Once a subplot is created, the axes are can be titled using the set_xlabel() (or set_ylabel()) method for the axes. plt.show() is called only when the entire figure is set up:

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

data = np.loadtxt('data/temperature.csv', delimiter=',')

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(5.0, 9.0))

axes1 = fig.add_subplot(4, 1, 1)

axes2 = fig.add_subplot(4, 1, 2)

axes3 = fig.add_subplot(4, 1, 3)

axes4 = fig.add_subplot(4, 1, 4)

axes1.set_ylabel('station 0')

axes1.plot(data[0,:])

axes2.set_ylabel('station 1')

axes2.plot(data[1,:])

axes3.set_ylabel('station 2')

axes3.plot(data[2,:])

axes4.set_ylabel('station 3')

axes4.plot(data[3,:])

plt.show(fig)

Temperature at each Station as Subplots

Moving plots around

Modify the subplot script to display the four plots as a 2x2 grid instead of as a stack.